Essay: Stringless Qin - Seeking the Roots of Silent Music by Emma-Lee Moss

Scenes from the Life of Tao Yuanming | Chen Hongshuo (Qing Dynasty; ink and colors on silk; Honolulu Museum of Art)

Of the legends attributed to Tao Yuanming, the Six Dynasties poet who gave up his role as a government official to live as a recluse, there is one that concerns the qin. Tao was said to have kept a qin, the seven-stringed zither which is today called the guqin, without strings on his wall. In a famous couplet, he wrote:

“If one grasps the deeper meaning of the qin, then why string it or try to make sounds?” (1)

For thousands of years, the qin was considered the supreme example of Chinese instruments, and a symbol of the literati (to play the qin was one of the “Four Gentlemanly Accomplishments of the Literati Lifestyle”) (2). Tao Yuanming’s poem alludes to the instrument’s greatest appeal - its relationship to personal and spiritual development. The qin was said to “restrain evil thoughts”; in literature, it was used by sages to manifest supernatural powers. (3)

In his book A Song for One or Two: Music and the Concept of Art in Early China, the musicologist Kenneth DeWoskin tells the story of Han Dynasty musician called Music Master Chuang, whose transcribes “mysterious music” with his qin resting on his lap: “He may have strummed responsively to the airborne tones as they came to him; more likely, however, his qin resonated responsively to the sounds as they came…It was a kind of hearing aid rather than a performing instrument.” (4)

In no part of the story is Music Master Chuang’s qin sounded or performed. Like Tao Yuanming, the master has achieved an understanding of the instrument that transcends the need for sound, best described by these lines:

“The fish-trap exists because of the fish; once you’ve gotten the fish, you can forget the trap.” (5)

Birth of Laozi (Detail; wall painting; Qingyanggong temple, Chengdu, China)

Next year marks the 70th anniversary of John Cage’s 4’33’’, the seminal work which is credited in Western music discourse as launching the concept of silent music.

To celebrate this, the musician Reylon will perform 4’33’’ on the yangqin, or hammered dulcimer, at London’s LSO St Luke.

Reylon is a founding member of Tangram, a UK-based music collective of artists who play both Chinese and Western instruments. Through musical projects, Tangram seeks to ‘cross the China-West divide, and explore the richness of diasporic experience’. It was with this in mind that Reylon first conceived of their performance, while considering the benefits of silence to cross-cultural barriers.

When 4’33’’ was premiered in 1952, it was performed by the pianist David Tudor. In transposing it to the yangqin, a traditional Chinese instrument, Reylon offers a critique accepted wisdom on the origins of silence as a musical experience. “As a Chinese instrumentalist,” Reylon says, “I am interested in studying and reclaiming the Daoist / Zen Buddhist roots of this performance of silence.” (6)

Tangram (credit: Zen Grisdale)

“Silence” has no direct translation in Chinese, but the concept of what Adrian Tien calls “non-sound” (7) has been discussed throughout Chinese history, alongside concepts of absence relating to other art forms and disciplines (as well as in other East Asian cultures such as Japan and Korea). In Chinese thought, silent discourse can be found in its three major belief systems – Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. In the latter way of thinking, simplicity in music was superior to all other virtues. In the Book of Rites, Confucius speaks of the “Three Withouts” - “music without sound, rites without embodiment, and mourning without garb” - as representing true mastery of each discipline. (8)

In Daoism, art in its most ideal form should reflect nature; sparseness in music represents the peaceful space of the natural world. The influence of Lao Tzu’s Da Yin Xi Sheng (大音希声, meaning Big Sound), referring to the cosmic flow of existence, contributed to what Reylon describes as “untimed, irregular, patternless or free” elements in Chinese music, which often includes inaudible or barely audible sounds. (9)

The concept of emptiness or absence is also a central tenet of Zen Buddhism, which evolved in China during Tao Yuanming’s lifetime and spread to Japan in the 12th century. Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy teaches in the Heart of Wisdom Sutra that “form does not differ from emptiness; emptiness does not differ from form.” (10)

In the Shurangama Sutra, Guanyin listens to waves washing up on a shore, until the sounds of waves are indistinguishable to the silence between them. She states: “I entered into the stream of the self-nature of healing, and thereby eliminated the sound of what was heard….Advancing in this way, both hearing and what was heard melted away and disappeared…” (11)

In the summer of 2020, WOMAD invited the guqin player Cheng Yu to Real World Studios, a recording studio on a canal boat near Bath. She was there as part of a digital version of the festival, which had been cancelled in the wake of the pandemic.

In one video, Cheng performs Wild Geese Descending on Sandbank, a guqin piece noted for its use of faint or inaudible notes, reflecting the real movement of geese disappearing on the horizon. Since its composition in at least the Northern Song dynasty, this famous composition has inspired countless paintings. In the Chinese tradition, ink painting is another art form which values absence; in paintings of Wild Geese Descending on Sandbank, the drop in volume could be said to be mirrored by large sections of liubai, or blank space. (12)

John Cage and Yoko Ono in Japan (with thanks to Madeline Bocaro)

The audio levels in Cheng’s filmed performance are mixed as though sensitive to the experience of a hypothetical listener, watching in person – the volume of the acoustic guqin is not boosted above those of the summery sounds of rural Southwest England. Between the few notes of the composition, and indeed during those notes, we hear the stereo sounds of a babbling water source. We hear birds chirping through the rustling of leaves. Cheng, also a member of Tangram, masterfully fulfils the guqin’s key virtue of he, or harmony. The instrument is played with peaceful balance, in spiritual harmony with itself and with the nature around it. The role of “background” noise is not assigned.

This experience sits comfortably with the more philosophical aspects of qin theory, and with Cage’s intentions for 4’33’’. Later in life, Cage still recalled the sounds that were heard during the premiere, including the sound of the wind outside, and the sound of people walking out of the concert hall. In his book Listen to This, Alex Ross describes Cage’s life as ruled by the thought that “all sounds are music”. “He wanted to discard inherited structures,” says Ross, “open doors to the exterior world.” (13) Cage famously believed that “there is no such thing as silence”, a belief underlined by his experience in Harvard University’s anechoic chamber, a soundproof room where, according to the writer David Toop, he heard “the high singing note of his nervous system and the deep pulsing of his blood”. (14)

Cage’s influences in Eastern mysticism are well-discussed, if often overlooked in appraisals of 4’33’’ cultural impact. His solo piano piece Music of Changes was composed using the I Ching, and his work is accepted to have been transformed after a visit to Japan arranged by Yoko Ono, who had noted the influence of Zen Buddhism in his music. (15)

Reylon, who also came to their performance of 4’33’’ after reading the Dao De Jing, wrote to me via email:

“Why do so many people give credit to Cage for coming up with this idea of “being still and listening” without acknowledging the East Asian philosophical influences at play?”

Fellow Tangram member Alex Ho wrote, “Narratives that assume Cage as the centre who implicitly conquered an East Asian philosophy, that itself is millennia-old, are frequent and misleading. Although not necessarily through Cage's own active shaping, this aligns with western classical music's long history of marginalising and misrepresenting East Asian cultures and identities.” (16)

~

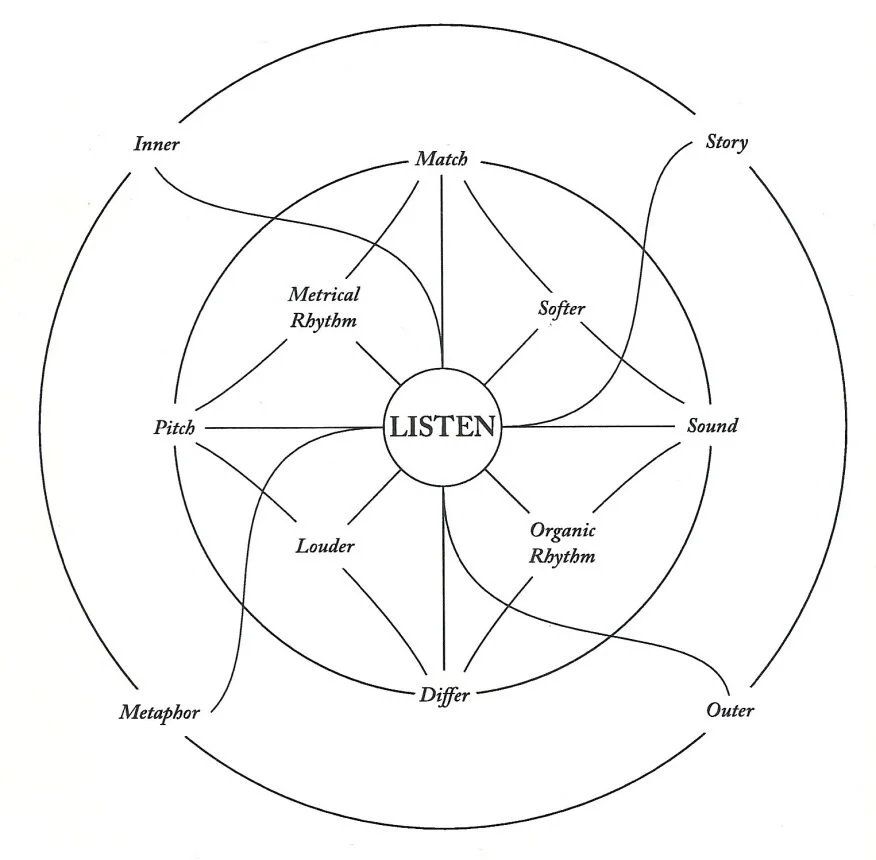

Every Sunday afternoon, I travel to an office building in Hackney to spend two hours online with people all around the world. Sometimes we sit or move in silence, sometimes we talk about sounds that we have enjoyed or ways that we have enjoyed them. We are students of Deep Listening®, a sonic practice developed by the composer Pauline Oliveros.*

Pauline Oliveros (credit: Vinciane Verguethen)

Oliveros, who died in 2016, was a contemporary and friend of John Cage’s. Despite her influence on contemporary music history as a performer, composer and mentor, she is not always found in the mainstream narrative of that history. To those who know her work, she is often spoken of with something akin to reverence.

Oliveros developed Deep Listening in collaboration with her partner IONE and the movement artist Heloise Gold. A Deep Listening practice involves exercises and meditations that encourage “360 degree” and “24-hour” listening. This might include listening with parts of your body other than your ears, and paying attention to sounds even while dreaming. To facilitate the practice, Oliveros wrote text-based scores, many of which resemble Zen koans, such as the meditation “Have You Ever Heard the Sound of an Iceberg Melting?”

I was drawn to Oliveros’ work after an ecstatic experience listening to ambient sounds while visiting my parents in Hong Kong. Learning that Deep Listening made use of Chinese movement practices, I signed up for one of two intensive courses at the Centre for Deep Listening®. In doing so, I hoped to combine an interest in ambient sound with questions concerning my own roots as a mixed-Chinese person who has lived in both the UK and Asia.

Like Cage, Oliveros was influenced by Eastern belief systems. A practitioner of Deep Listening is encouraged to think of Chinese medicinal principles such as meridians, while movement meditations drawn from Tai Chi and Qi Gong are part of the daily practice. (17) The result is not literally a musical experience but more closely aligned with healing and personal transformation. Much like the non-sounding qin, the aim is not particularly related to heard sounds, but a deeper, more full definition of where listening can take you.

Wind Horse | Pauline Oliveros with additional design by Lawton Hall (1990; text score)

Tracy McMullen describes Oliveros and Cage’s differing engagements with Eastern spirituality in her essay Subject, Object, Improv: John Cage, Pauline Oliveros and Eastern (Western) Philosophy in Music. Cage, she says, had a “preference for the mind and sublime over the body to connect it to his Protestant-informed religiosity”, despite a lifelong engagement with Zen Buddhism. She adds, “Cage took the Zen exhortation of selflessness and placed it in a Kantian, modernist context—one that was eminently authoritarian.” (18)

In contrast, Oliveros, who by the end of her life was increasingly devoted to Tibetan Buddhist practice, “encouraged a type of meditative attention and awareness that would foster creative and nuanced responsiveness in an improvisatory setting.” (19) She rooted Deep Listening in an embodied practice that encouraged both improvisation and collaboration. When practicing her meditations, one locates sounds and emotions that cross both temporal limits or states of being, by bringing awareness to the body. Openness and shared authorship being a proponent of her work, her influences feel easier to access and discover.

McMullen opens her essay with a musing that perhaps explains why - other than the fact she was a woman - Oliveros’ reputation remains somewhat underground. She says that music “poses a problem for a Western intellectual tradition that privileges reason and the mind over the body…champions of music as a “serious art” have often been at pains to associate it with the privileged “mind side” of the Western mind-body split.” (20)

I don’t see Cage himself as an authoritarian. He was no stranger to marginilisation as a queer man and avant-garde artist, who often funded his practice through mycology. (21) However, I see the limits of the system in which he practiced and under which his legacy has been appraised. A cultural obsession with 4’33’’ as a single watershed event, or a literal interpretation of its intentions, can narrow the potential of what we find in silence. Reaching for its roots, we might find new ways of interpreting the meaning of both silence and sound.

~

RAYMOND ANTROBUS:

As a deaf person in the hearing world I know that there is no universal experience of sound. So how can we capture what it is? How do we turn sound into words? What is sound?

MEG DAY:

[laughs] Oh… [sighs] It’s a... I think it's a kind of mythology. It's, um, it's an inherited form, maybe. Just another way to [takes a deep breath] to understand the world? Deaf poet Ilya Kaminsky and I have talked a lot about sound being an invention of the hearing. Silence too. I think often about how our common understanding of sound is that it is natural and given and compulsory that it's just a thing that, um, I don't know occurs to us? [laughs] But if it is that sound is, you know, waves knocking around in the cave of one's head, and then processed in some kind of approximated but not necessarily universal way, then isn't sound just a metaphor? It's one way for experiences to touch.

- annotated transcript of Inventions in Sound, BBC Radio 4 documentary presented by Raymond Antrobus (22)

In Ocean of Sound, David Toop dismisses the idea that 4’33’’ was inspired by Zen Buddhism, highlighting the impact of Cage’s experience in the anechoic chamber on the genesis of his idea. I would argue that there’s no need to choose.

In fact, the roots of silence stretch further back than we can imagine. Musicologist Shzr Ee Tan reminds me that, an indefinite amount of time before Cage, or even Wild Geese Descending on Sandbank, “indigenous cultures in different parts of the world were already listening to 'absence-as-presence' - whether birds in the rainforest as portents of weather or of agricultural cycles, or of spiritual cosmologies.” (23) In an article about folksongs of the Bunun People of Taiwan, she writes about a song that “fades up” from imperceptible sounds to crescendo, representing the growth of millet crops. (24)

When I sit in silence, I hear the texture of the world, and the sonic landscape of my memories. I hear a constant ringing in my ears that is louder when I’ve had caffeine or a sleepless night – an experience of tinnitus that convinces me that caffeine in itself is a sound. When I feel anxious, I hear fewer sounds. When my shoulders relax, I hear my own thoughts more clearly.

Resistance Postcard | Christine Sun Kim (2017; postcard; 10 x 15; Primary Information)

Reylon tells me, “There is so much we can learn from silence, both personally and collectively. Silence is deeply linked with a state of listening. Going beyond a physical definition that excludes those who are d/Deaf, I believe listening involves openness, receptiveness, and presence. Maybe silence is presence.” (25) For this, I consider the Chinese word jing, a close translation for “silence” which means quiet, calm or still.

Adrian Tien writes that, in Chinese sonic experience, there was a high expectation on the listener to “think beyond the sonic form”, “ie hearing with something other than the ear”. (26) I think of Tung-Kua Ya, the Qin Dynasty sage who hears a general’s unspoken plans by “examining his composure” (27) I imagine Cage in the anechoic chamber. When we say he heard his body processes, perhaps we simply mean that he knew that they were there; he experienced the safety and certainty of the pulse of his blood, its tempo knocking against his skin.

In this text, I have spent a lot of time on Chinese ideas of silence which, while helpful for understanding and expanding our own language of silence and sound, are rooted in hierarchy. Literati culture in China was built on the idea of an isolated, lofty scholar class, a Confucianist system of thinking that still affects the way women are perceived in the arts. This has its analogies in the Western art world, where long-established patriarchal norms are still being unpicked. There are other parallels too: for anyone who has heard 4’33’’ critiqued as pretentious, it is amusing to think that scholars such as Tao Yuanming were also derided by those who just wanted to hear familiar tunes on a well-played qin. (28)

Still, I find a great deal of potential when we examine these concepts. DeWoskin writes that, in “Chinese cosmogenic theory, sound in its primal state was inaudible.” (29) Heard music was simply the echo of that silent, original sound. Taking into account the idea that “all sounds are music”, what we hear when we sit in present stillness are the echoes of the original sound.

No wonder those who experience silent music report transformative experiences. In Ocean of Sound, David Toop describes heightened auditory awareness gained after “sparse tones” of the suikinkutsu, the Japanese water feature and instrument, for which “silence in the point”. (30) Meanwhile, my own experience of Deep Listening has had a surprising effect on my interactions with people around me. These days, I am more able to understand the things we can’t communicate with words.

The sound artist Christine Sun Kim, interviewed by Raymond Antrobus for BBC Radio 4, asks, “Does sound itself have to be a sound? Could it be a feeling, emotion or an object? Could time itself become a sound?” (31) We can begin to answer these questions by cultivating stillness, and by offering our presence to each other. No matter how you find your way to silence, the potential remains the same. When I tell you that I hear you, it means I know you’re there.

*Deep Listening® is written here with the symbol to denote that it is a registered trademark, in part to separate it from other forms of deep listening, such as relating to meditation or mediation. I have used it twice in the text, but it applies to all mentions throughout.

Emma-Lee Moss is a writer and musician.

Essay published as part of the Orchid Pavilion’s series Immaterial

1 Carpenter, John T., Oka, Midori – The Poetry of Nature: Edo Paintings from the Fishbein-Bender Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018 (p. 85)

2 Tien, Adrian – The Semantics of Chinese Music, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2015 (p. 183)

3 DeWoskin, Kenneth J. – A Song for One or Two, Center for Chinese Studies, the University of Michigan, 1982 (p. 117)

4 ibid. (p. 138)

5 ibid. (p. 140)

6 Email interview with Tangram members Reylon, Alex Ho, Sun Keting

7 Tien, Adrian – The Semantics of Chinese Music, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2015 (p. 38)

8 DeWoskin, Kenneth J. – A Song for One or Two, Center for Chinese Studies, the University of Michigan, 1982 (p. 138)

9 Email interview with Tangram members Reylon, Alex Ho, Sun Keting

10 The Heart Sutra – https://plumvillage.org/about/thich-nhat-hanh/letters/thich-nhat-hanh-new-heart-sutra-translation

11 Dr. Shen, Chian Theng – The Enlightenment Of Bodhisattva Kuan-Yin (Avalokiteshvara) Part I, Delivered at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii February 26, 1982

12 Tien, Adrian – The Semantics of Chinese Music, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2015 (p. 37-40)

13 Ross, Alex – Listen to This, Fourth Estate, 2010 and 2011 (p. 265)

14 Toop, David – Ocean of Sound, Serpent’s Tail, 1995 (p. 141)

15 Bocaro, Madeline – Yoko and John…Cage https://madelinex.com/2018/09/05/yoko-and-john-cage/

16 Email interview with Tangram members Reylon, Alex Ho, Sun Keting

17 Gold, Heloise – Deep Listening Body, Deep Listening Publications, 2008

18 McMullen, Tracy – Subject, Object, Improv: John Cage, Pauline Oliveros, and Eastern (Western) Philosophy in Music, Critical Improv, vol. 6 no. 2 (2010)

19 ibid.

20 ibid.

21 Ross, Alex – Listen to This, Fourth Estate, 2010 and 2011 (p. 273)

22 Antrobus, Raymond – Annotated transcript, Inventions in Sound, Falling Tree Productons for BBC Radio 4, 2021

23. Interview with Dr. Shzr Ee Tan

24. Tan, Shzr Ee – The Bunun of Taiwan: a Shimmering Harvest, Offstage, 2019

25 Email interview with Tangram members Reylon, Alex Ho, Sun Keting

26. Tien, Adrian – The Semantics of Chinese Music, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2015 (p. 46)

27 DeWoskin, Kenneth J. – A Song for One or Two, Center for Chinese Studies, the University of Michigan, 1982 (139)

28 lore of the lute 109

29 DeWoskin, Kenneth J. – A Song for One or Two, Center for Chinese Studies, the University of Michigan, 1982 (p. 138)

30 Toop, David – Ocean of Sound, Serpent’s Tail, 1995 (p. 156)

31 Antrobus, Raymond – Annotated transcript, Inventions in Sound, Falling Tree Productons for BBC Radio 4, 2021