Essay: On Immateriality in Guo Xi's Early Spring by Alex Whittaker

Introduction

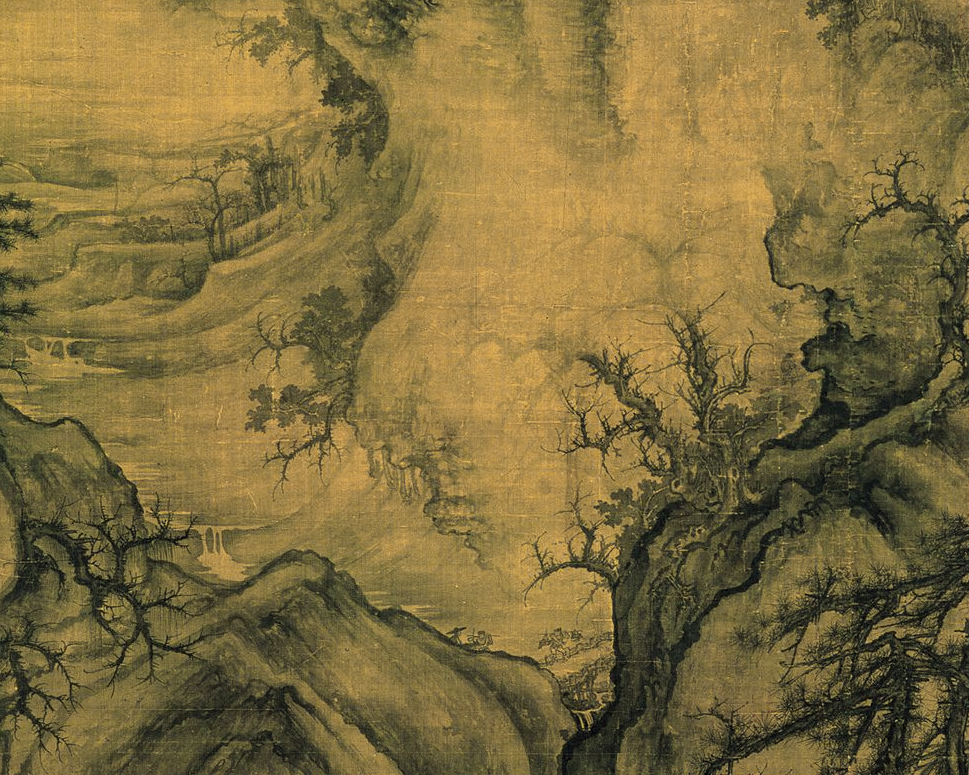

The ink painting Early Spring, painted by Guo Xi in 1072 (Fig. 1), is one of the most famous and reproduced of the Northern Song paintings in the monumental landscape tradition. (1) The artwork is currently mounted as a hanging scroll on display at the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Completed during the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279), the original context for viewing this work is likely to have been a hall of the Imperial Palace under Emperor Shenzong (r. 1068 – 1085), where it was intended to be viewed by the ruler himself, or those in his company at Kaifeng. (2) The capital of the Northern Song dynasty was a place “where imperial palaces, government offices and high-ranking official residences were richly decorated”. (3) Early Spring can be considered as a relatively rare example of an artwork commissioned for the imperial courts, for it was here that Guo Xi served, in one of the institutions devoted entirely to painting and calligraphy. (4)

Whilst the image is currently mounted as a hanging scroll, it is possible that the artwork originally existed as a screen, simultaneously dividing space and functioning as a backdrop to daily life. It is also possible that the work existed as a series of four paintings, and that the paintings depicting summer, autumn and winter were subsequently lost. However, without evidence, we are left to simply speculate. For the sake of clarity, the first part of this text will look closely at the social and historical configurations that produced Early Spring and the role of the viewer. The second will focus predominantly on an analysis based on material evidence. Finally, I will address concepts of immateriality and meaning in the painting and how these meanings might change against the backdrop of a shifting cultural landscape.

Fig. 1 Early Spring | Guo Xi (dated 1072; hanging scroll, ink and light colour on silk; 158.3 x 108.1 cm; National Palace Museum, Taipei)

Origins

The Song dynasty (960-1279) has been recorded as the golden age of Chinese painting. (5) The supreme forms of expression were calligraphy and painting, and, by the tenth and eleventh centuries, landscape painting (shanshui hua, literally “mountain and water” painting) emerged as the most important subject. (6) Here, the depiction of landscape as subject matter for its own sake reached its apex and the trope of natural realism became ever more sophisticated. Painters were seen to straddle the shared disciplines of the “arts of the brush” – both painting and calligraphy alike. It is also during this period that painted imagery began to reflect the more gestural and expressive mark-making commonly seen in calligraphy. A more general theory of painting was created, which elaborated a distinction between amateur scholars and the more professional artisan painters. (7) Scholars upheld the value of spontaneity and concerned themselves less with the accurate depiction of nature. For them, painting was a social activity to be practiced alongside poetry and calligraphy. However, Early Spring appears to be born out of a set of more artisanal concerns, whereby equal weight is given to veracity of representation, made manifest in the “meticulous” style.

Fig. 2 The Classic of Filial Piety (detail) | Li Gonglin (ca 1085; handscroll, ink and colour on silk; 23.2 x 497.8 cm; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Writing on painting also proliferated during this time, and the thoughts and concerns of artists are particularly well documented. (8) The text Linquan Gaozhi (The Lofty Truths of Forests and Streams) comprises a series of conceptions to do with shanshui painting, put together by Guo Xi’s son, Guo Si – himself a scholar-official. (9) Guo Si stated in the preface to the Linquan Gaozhi that, from an early age, he was accustomed to noting down his father’s opinions on art. According to him, Guo Xi would often wander around sketching the natural scenery and had studied Daoism in his youth. (10) The figure of the artist here is of solitary wanderer communing with nature through the act of walking, sketching, and simply being “at one”.

However, artists such as Guo Xi, whilst in the service of the commissioning patrons, still had to formulate a distinctive language that would be both characteristic of and instantly recognisable to an educated official group. Painting itself became pressed into the service of moral, social or even hierarchical power structures of the day. (11; Fig. 2)

Scarlett Jang has written that the meanings of these works connected directly with the status and concerns of the figures who commissioned them – the Emperor, for example, and the “academicians who traditionally served as the Emperors’ advisors”. (12) The supposition here is that Early Spring was born out of a set of pre-existing and established hierarchical values. Furthermore, the Jade Hall at the Emperor Zhezhong’s court comprised of paintings that were “intended to allude to the jade hall referred to in Daoist literature as the residence of the Immortals”. (13) This compounds the idea that the language of Northern Song monumental landscape is bound up with a narrative of power. The narrative here though is to be found in and sustained by the viewers themselves, rather than embedded in the painting by the artist. In this sense, when considering who made the work, we might simultaneously be asking who the work was made for. Chinese painting commissioned for the courts intended to reflect back the self-same values of the viewers.

In art, this is nothing new. However, it’s worth noting Jonathan Hay’s proposition – that viewers are essentially conditioned by the social and cultural context from which they are produced. This includes us as modern-day viewers as much as it does the late tenth century viewers of the imperial court. He says that “for a viewer conditioned by the truth claims of photography, it is hard to resist the reality effect produced by a highly developed rhetoric of veracity”, and that “modern scholarship has often sought to identify early Song naturalism as a proto-scientific objectivity of observation.” (13) He goes on to say that “while this quality is by no means absent…equally relevant as a general context for naturalism in late tenth-century China are the very different truth claims of visualisation practices associated with neo-Confucianism, in which vision was variously associated with access to a deeper, normally hidden reality. Under the Northern Song, this access became aligned with optical experience.”

Hay is talking about the precepts of the viewer in the context of neo-Confucian thought, and the “normally hidden reality” he describes here is power. The imperial courts acted as centres of cultural power, and that power was expressed through distinctive visual systems, in both clothing and painting, in order to make the invisible visible. Perhaps the most successful way to derive a distinctive visual system that connotes societal order is for that same system to be instantly recognisable and characteristic of the order that it represents. There is an equivalence between the contemporaneous viewer, conditioned by the “truth claims” of photography, and the imperial court viewer, whose own bias might have been to read Early Spring in terms of its “truth claims” regarding the perceived “natural” structures of imperial power as “aligned with optical experience”. (15)

Craig Clunas talks about an anecdote, perhaps best known to Persian speakers, in which Alexander the Great is found to be in dispute with the emperor of China over the merits of Greek and Chinese artists. In the story, a competition is organised between the two nations where two teams of artists work at opposite ends of a room divided by a curtain, which reveals two identical paintings once drawn aside. It eventually becomes apparent that the Chinese artisans have polished their wall to such a great level of perfection that it reflects back the Greek painting exactly. All of this occurs in a context where the act of reflecting carries positive associations of revealing the will and purposes of God. (16) Early Spring can perhaps also be seen as a mirror in this same way, revealing and reflecting otherwise unseen structures of power back to its attendant audience. The audience or viewer in this instance is both privy to and complicit in the very same social structures. It is here in this relationship between artist, artwork, and audience that we can start to understand who this work was for and how its message can be designated.

Material

To the top right-hand side of the image is an inscription, added to the silk surface by the Qianlong Emperor in 1759 (Fig 3.). The inscription occupies a prominent position over the top right-hand side of the mountain crest, making it almost impossible to see the image without encountering the text, which reads as per the contemporary translation below;

Fig. 3 Early Spring | Guo Xi (detail)

“The trees are beginning to sprout leaves, the frozen brook begins to melt,

A building is placed on the highest ground, where the immortals reside,

There is nothing between the willow and the peach trees to clutter up the scene,

Steam-like mist can be seen early in the morning on the springtime mountain “(17)

We know from this that the painting was held in high regard, at least from its conception through to the point at which it was viewed by the Qianlong Emperor in 1759 – who was so taken by the image that he rendered his own creative response upon its very surface. It seems, for this period at least, that the meaning and message of the painting remained the same.

When the Qianlong Emperor talks of ‘trees beginning to sprout leaves’ and that the “frozen brook begins to melt” he is again emphasising the temporal nature of the image. We already know that the premise of ink painting was often an attempt to describe the passage of time, in spite of its essentially anachronistic nature. However, we can go further than that; the Emperor also talks about there being “nothing between the willow and peach trees to clutter up the scene”, alluding to a clarity or poise of vision “in the morning on the springtime mountain”, doubly underscoring the fact that this is a great moment of unfolding promise in both the time of day and the season. It is hard not to equate the notion of clarity of vision and of prosperity for the future with the aspirations of political leadership towards benevolent rule. In the context of Emperor Shenzong’s court, for example, moral and cultural cultivation measured by a system of examinations in the Confucian classics actually ensured the right to rule. (18)

Fig. 4 Early Spring | Guo Xi (detail)

To the left of the crest of the mountain, and somewhat dominating the overall image, is the Qianlong Emperor’s seal (Fig. 4) This is the largest seal visible on the work, which documents his own presence and viewing of the painting succinctly with 乾隆 Qianlong, 御 imperial, 覽 viewing, 之寶 treasure.

The outer fringes of the silk ground show many more seals, indicating either previous or subsequent viewings of the artwork by other officials throughout the course of the artwork's history, allowing us as viewers to trace the journey of the artwork through time. None of the seals cover or interfere with the brushwork of the artist and all have been placed in large swathes of the painting which have been left white to suggest mist, clouds or simply “nothingness”. (19) The painting itself depicts a detailed landscape comprised of several viewpoints, montaged together using a strategy termed by the artist as the "angle of totality”. Here the viewer is situated at the threshold of three spatial relationships: 高遠 gaoyuan (vertical distance),深遠 shenyuan (deep distance) and 平遠 pingyuan (horizontal distance). (20) It is this combination of vantage points – looking “up” at the mountain, “down” at the valley and “through” the horizon line to an indeterminate point in the distance – that gives Early Spring both its temporal and lyrical qualities. These qualities situate the viewer in active relationship to the work, approximating the act of being in, and at one with, the very movement and rhythm of nature itself.

Early Spring is one of the earliest surviving landscape paintings constructed in black ink alone, without the inclusion of any other colours. (21) Only white pigment, very lightly tinted with blue, was also used to emphasise form and the occlusion of light which naturally occurs when looking at a landscape over great distances. Constructing the image in predominantly black ink allowed Guo Xi to focus on depicting the landscape or form through the variation of tonal values. Black ink, originally found in the form of an inkstick, was ground down upon an inkstone and combined with water to produce an intense jet-black pigment. Inksticks – a convenient form of solid ink – were produced by consolidating the carbonised, blackened soot or ash from pinewood with animal glue. Or, more commonly, comprised natural minerals such as graphite, which could also be ground on a stone and mixed with small amounts of liquid. The tone of the pigment could then be adjusted depending upon the concentration of the solution itself. Using this simple technique, painters such as Guo Xi were able to elicit a full gradient of tones from black through to a barely perceptible, semi-opaque tinted wash – whereby the pure white of the silk contrasted starkly with the intense black of the pigment. By building consecutive layers of ink upon silk in this way, the brushwork of Early Spring forms an image of meticulous construction, almost devoid of expressive or gestural mark-making. Scale and physicality of the landscape is emphasised as subject matter, purely for its own sake. Figures and depictions of architectural structures are rendered secondary and indeterminably small in scale against the backdrop of an epic natural world.

There is a great emphasis on painterly detail evident in Early Spring. However, it is worth noting that the tools and brush technique bear a direct relationship to the act of calligraphy – the artwork or image as a site of process whereby natural, even bodily, forces of movement and gesture are enacted on the surface of the silk. Certainly, it is true that authorship here is important, if we are to read the work as a mediation of Guo Xi’s own experience of nature, directly attributable to him. However, the materials and method used activate the imagery far beyond the artist’s subjective concerns. In Early Spring, we see meticulous attention to detail in Guo Xi’s characteristic rendering of bare and sparse “crab claw” trees (Fig. 5), but we see none of the obsessive “all over” detail that has been applied to Fan Kuan’s Travellers among Mountains and Streams (Fig. 6, 7).

Both artists approach chiaroscuro through their brushwork but to very different ends, depending on their chosen method. Fan’s work is tonally “flat” in relation to Guo’s dramatic contrast. Fan Kuan fills in form with repetitive, tiny brushstrokes, combining line with tone through mark-making alone, where Guo pushes form outwards from the edge of a single brushstroke – negative space becoming positive with the simple turn of the brush. Here, Guo’s gestural marks appear on an apparently sliding scale between the meticulousness of Fan Kuan and the visually expressive nature of calligraphy itself.

Fig. 7 Travellers Among Mountains and Streams | Fan Kuan (c 1000)

Immaterial

In the Linquan Gaozhi, Guo Si notes from Guo Xi that “a mountain seen from nearby appears a certain way; seen from a distance of several miles, it appears another way; seen from a distance of several tens of miles, it appears yet another way. For each distance it has a different appearance. This is what we call: ‘the mountains form changes with each step’.” (22)

Guo Xi describes a temporal experience of being in the world. He emphasises not just the fact that the formal aspects of mountain scenery change through our proximity to it, but also that this physical relationship has an equivalence to visual perception. The mountain does not exist in isolation but rather it exists in an active and participatory relationship to the viewer, changing and unfolding – revealing its form ever more fully as our engagement with it shifts through space and time.

It is fair to assume that Guo Xi’s rendering of a mountain attempts to carry with it the same temporal dimension of lived experience in a landscape. As viewers, we are invited to approximate the same experience of changing distances, time, and of “being in nature” in much the same way that it was experienced by Guo Xi in the moment. Indeed, we noted earlier that he himself wandered the landscape sketching and studied Daoism in his youth – perhaps one explanation for the ethereal and otherworldly “spiritualism” evidenced by the language used in the Linquan Gaozhi. Either way, there is the very real supposition here that the painting functions as a kind of “stand-in” or simulation for the very real experience of moving through nature. It is noteworthy too that the city of Kaifeng had approximately one million inhabitants at the time, a sprawling metropolis by Song, if not global standards. The simulation of communion with nature may have felt even more prescient, given the proximity of the court and its officials to the urban development of the capital.

“Mountains in the morning look a particular way; in the evening, they look another way; when it is cloudy or clear, they look yet another way. This is called ‘the changing appearances of morning and evening are not the same’. Thus, one mountain expresses the attitudes of several thousand mountains. Should we not thoroughly investigate this?” (23)

In this beautiful passage, Guo Xi effectively personifies the mountain in the sense that it too might be alive and able to express itself, again situating the otherwise inanimate in active participation with the viewer. Importantly, he reconciles the individuality of one mountain, with its possibility to express characteristics of all mountains in the changing qualities of its formal characteristics, through time. All mountains can be one and one, can in fact, simultaneously be all – undeniable and unequivocal in their monumentality. This surely must also be read as an argument for the totality of natural order and that we too, as viewers, are made pious by its presence. This sentiment may or may not be echoed in the tiny, almost insignificant depictions of human figures in the landscape itself. As far as we know, the landscape in Early Spring is not specifically attributable to any one range of peaks in northern China. It is much more likely that this is a hybrid or montaged view of several peaks and valleys studied previously by Guo Xi. It is an idealised and composite image that alludes to the experience of mountains rather than the mountain as a singular experience. Its themes then are universal, reflected in the fact that this would ultimately be a work on public display to officials in close proximity to the Emperor.

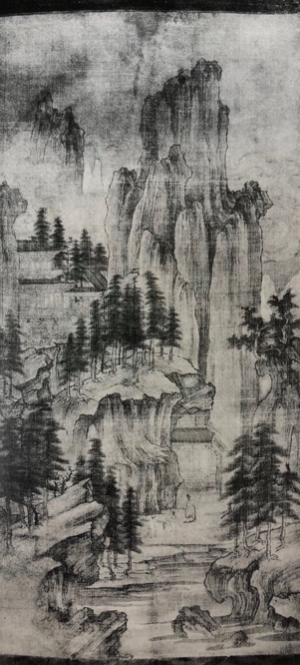

As Craig Clunas noted in Art in China, scholarship in the field of very early landscape painting in China has often been hampered by the very low survival rate of good examples. Research has often leaned heavily on the discovery of large numbers of Buddhist paintings from the caves of Dunhuang and on much later copies of works prior to around 1000 CE. (24) If anything, this has served to lend greater significance to Early Spring, not least because we’re are much more acutely aware of the life of its author and the attendant cultural context. Looking back further than that, the view is increasingly misty, with some good exceptions. The anonymous landscape on silk (Fig. 8) was excavated from a tomb of an aristocratic woman alive in the second half of the tenth century CE. (25) Unlike Early Spring, the depiction of landscape here is far less hinged upon an objective interpretation of landscape, and the work itself appears more subjective and more stylized than its counterpart. The anonymous landscape reads far more as a “dreamscape” or Daoist mountain paradise, inhabited perhaps by immortals. Its inclusion in a tomb has, for some, suggested that this might have been hung as a wish for safe passage into the afterlife for the dead woman. Perfunctory formal comparisons notwithstanding, the suggested role or function of the painting here is clear; imagery takes on talismanic properties, connecting the viewer with a deeper, previously unseen reality or spiritual truth about our place in the universe.

Fig. 8 Anonymous Landscape (Hanging scroll, ink and light colour on silk)

Alexander Whittaker is a director of Pavilion Gallery. A visual artist and trained art historian, he is currently studying for a Diploma in Asian Art at SOAS

Essay published as part of the Orchid Pavilion’s series Immaterial

Footnotes:

1 Clunas, Craig – Chinese Painting and its Audiences, Princeton University press 2017 p.84

2 Ibid

3 Jang, Scarlett - Realm of the Immortals: Paintings Decorating the Jade Hall of the Northern Song, Ars Orientalis, 1992, Vol. 22 (1992), p. 81

4 Clunas, Craig – Art in China, Oxford University Pres 1997 p54

5 Bush, S & Shih, H – Early Texts on Painting, Hong Kong University Press 2012 Ch.3

6 Murashige, Stanley – Philosophy of Art, Encyclopaedia of Chinese Philosophy, 1st Edition, Routledge 2003

7 Clunas, Craig – Art in China, Oxford University Pres 1997 p141

8 Bush, S & Shih, H – Early Texts on Painting, Hong Kong University Press 2012 Ch.3

9 Guo Si shall hereon be considered the author of The Linquan Gaozhi

10 Clunas, Craig – Art in China, Oxford University Pres 1997 p142

11 The Classic of Filial Piety by Li Gonglin (Fig. 2), a handscroll painted approximately ten years after Early Spring reflected a moral purpose – that piety in the home both precedes and promotes a harmonious engagement with the wider world. The text eventually became bound up with the neo-Confucian canon.

12 Tang, Scarlett Ars Orientalis, 1992, Vol. 22 (1992), pp. 81-96

13 ibid

14 Hay, Jonathan – The Mediating Work of Art, The Art Bulletin, Sep 2007, Vol 89, No. 3 September 2007 p.441

15 Ibid

16 Clunas, Craig – Chinese Painting and its Audiences, Princeton University press 2017 p.12

17 Translated by Blossom Moss, Hong Kong, February 2021

18 Clunas, Craig – Art in China, Oxford University Pres 1997 p141

19 Whittaker, Alexander – Force of Nature, interview with Hung Hoi, Pavilion Journal, July 2020, https://www.paviliongallery.com/pavilionjournal

20 Hoi, Hung – Force of Nature, interview with Alexander Whittaker, Pavilion Journal, July 2020, https://www.paviliongallery.com/pavilionjournal

21 Clunas, Craig – Art in China, Oxford University Pres 1997 p53

22 Murashige, Stanley – Rhythm, Order, Change and Nature in Guo Xi’s Early Spring, Monumenta Serica, 1995, Vol. 43 (1995), pp. 338Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Originally printed in Linquan Gaozhi p.635

23 Ibid

24 Clunas, Craig – Art in China, Oxford University Pres 1997 p54

25 Ibid p53

Bibliography

Bush, Susan and Shih, Hsio-yen – Early Chinese Texts on Painting, Hong Kong University Press, 2012

Clunas, Craig – Art In China, Oxford University Press, 1997

Clunas, Craig – Chinese Painting and its Audiences, Princeton University Press, 2017

Confucius - The Analects, translated by DC Lau, Penguin, 1979

Harrist, Robert E. – Art and Identity in the Northern Sung Dynasty: Evidence from Gardens, in Arts of the Sung and Yuan. P. 147 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996

Hay, Jonthan – The Mediating Work of Art, The Art Bulletin, Sep., 2007, Vol. 89, No. 3 (Sep., 2007), pp. 435-459, The Art Bulletin , Sep., 2007, Vol. 89, No. 3 (Sep., 2007), pp. 435-459, CAA

Hoi, Hung – Force of Nature, interview with Alexander Whittaker, Pavilion Journal, July 2020,

Nisbett, Richard E. – The Geography of Thought, How Asians and Westerners Think Differently and Why, Nicholas Brealey, 2003

Lao-tzu – Tao Te Ching, translated by Stephen Mitchell, Harper Row, 1988

Little, Stephen with Eichman, Shawn – Taoism and the Arts of China, University of California Press, 2000

Murashige, Stanley – Rhythm, Order, Change and Nature in Guo Xi’s Early Spring, Monumenta Serica, 1995, Vol. 43 (1995), pp. 337-364 Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

Murashige, Stanley – Philosophy of Art, Encyclopedia of Chinese Philosophy, 1st Edition, Routledge, 2003

Ping Foong – Guo Xi's Intimate Landscapes and the Case of "Old Trees, Level Distance", Metropolitan Museum Journal, The University of Chicago Press, 2000, Vol. 35 (2000) pp. 87-115

Shih, Shou-Chien – Beyond the Representation of Streams and Mountains: The Development of Chinese Landscape Painting from the Tenth to the Mid-Eleventh Century

Tang, Scarlett – Ars Orientalis, 1992, Vol. 22 (1992), pp. 81-96

Wen C. Fong – Beyond Representation, Chinese Painting and Calligraphy 8th – 14th Century, chapter: Of Nature and Art: Monumental Landscape Painting, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992

Wong, Eva – Taoism, An Essential Guide, Shambala, 2011

Image References

Fig 1. Early Spring, Guo Xi, dated 1072

Hanging scroll, ink and light colour on silk

158.3 x 108.1 cm

National Palace Museum, Taipei

Image accessed at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Guo_Xi_-_Early_Spring_(large).jpg

Fig. 2 The Classic of Filial Piety, Li Gonglin ca 1085 (Detail)

Handscroll, ink and colour on silk

23.2 x 497.8 cm

The Metropolitan museum of Art, New York,

Accession Number: 1996.479a–c

Image accessed at https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/39895

Fig 3. (Detail) Early Spring, Guo Xi, dated 1072

Hanging scroll, ink and light colour on silk

158.3 x 108.1 cm

National Palace Museum, Taipei

Image accessed at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Guo_Xi_-_Early_Spring_(large).jpg

Fig. 4 (Detail) Early Spring, Guo Xi, dated 1072

Hanging scroll, ink and light colour on silk

158.3 x 108.1 cm

National Palace Museum, Taipei

Image accessed at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Guo_Xi_-_Early_Spring_(large).jpg

Fig 5 (Detail) Early Spring, Guo Xi, dated 1072

Hanging scroll, ink and light colour on silk

158.3 x 108.1 cm

National Palace Museum, Taipei

Image accessed at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Guo_Xi_-_Early_Spring_(large).jpg

Fig. 6 (Detail) Travellers Among Mountains and Streams, Fan Kuan, c 1000

Hanging scroll, ink and light colour on silk

206.3 x 103.3 cm

National Palace Museum, Taipei

Image accessed at https://www.comuseum.com/painting/masters/fan-kuan/travelers-among-mountains-and-streams/

Fig. 7 Travellers Among Mountains and Streams, Fan Kuan, c 1000

Hanging scroll, ink and light colour on silk

206.3 x 103.3 cm

National Palace Museum, Taipei

Image accessed at https://www.comuseum.com/painting/masters/fan-kuan/travelers-among-mountains-and-streams/

Fig. 8 Anonymous Landscape

Hanging scroll, ink and light colour on silk

Excavated from the tomb of a woman believed to have been alive in the second half of the 10th century CE

Printed in Clunas, Craig – Art in China, Oxford University Press, 1997 p53